The most obvious sign that Deepwater Wind is about to start installing the nation’s first offshore wind farm appeared in the Atlantic Ocean waters near Block Island on Saturday.

The most obvious sign that Deepwater Wind is about to start installing the nation’s first offshore wind farm appeared in the Atlantic Ocean waters near Block Island on Saturday.

It’s hard to miss, coming in the form of the 300-foot-long Weeks 533, the largest water-borne revolving crane on the East Coast.

In the 1960s and ’70s, the floating crane was used to build bridges in California and Oregon, and in the 2000s, after being moved cross-country and repurposed, it retrieved the US Airways plane that famously crash-landed on the Hudson River and lifted a Concorde jet and the space shuttle Enterprise onto the deck of the Intrepid Sea, Air and Space Museum in Manhattan.

Workers with New Jersey-based Weeks Marine and Manson Construction, of Seattle, won’t be using the 500-ton capacity crane with its 210-foot boom to move anything as exotic as a supersonic plane or a spacecraft for Deepwater. But early this week, when they’re scheduled to carefully pick up the first steel foundation for the five-turbine Block Island Wind Farm and slowly lower it into place, they still will be working on something completely new to this country.

The work taking place in the waters about three miles southeast of the island will kick off marine construction for a test project that has been in the planning stages for almost a decade and aims to prove the viability of offshore wind power in the United States. The people at Providence-based Deepwater describe the long-awaited milestone as “steel in the water.â€

Until now, all of the work has taken place on land, and everything has gone smoothly. But the list of potential problems increases when you go offshore.

“At the end of the day, we’ll have five turbines running, that’s for sure,†said Jens Hansen, project director for Deepwater who in previous jobs has overseen the installation of eight offshore wind farms in Europe. “But the biggest challenge is to keep to the timeline.â€

A choreographed dance

It’s a challenge because the first lift kicks off a mind-boggling series of maneuvers that will take place around the clock over the next eight weeks.

Think of it as a tightly-choreographed dance involving two smaller floating cranes — the Weeks 526 and the Weeks 571 — as well as a host of tug boats, support vessels.  It will also include the transport barges carrying the foundations from a building yard in Louisiana.  As one crane barge completes one step, another takes its place for the next, then a new one comes in for a different move and so on and so forth.

When it all begins depends on when the first transport barge gets to the project site. As of Saturday afternoon, the barge — carrying two lower “jacket†sections of the foundations, one upper deck section and piles that will secure the structures to the ocean floor — was just south of Block Island.

Before it sets up at the project site, crews with Weeks Marine and Manson Construction will mark off the area, put moorings in place and get ready to start the heavy work.

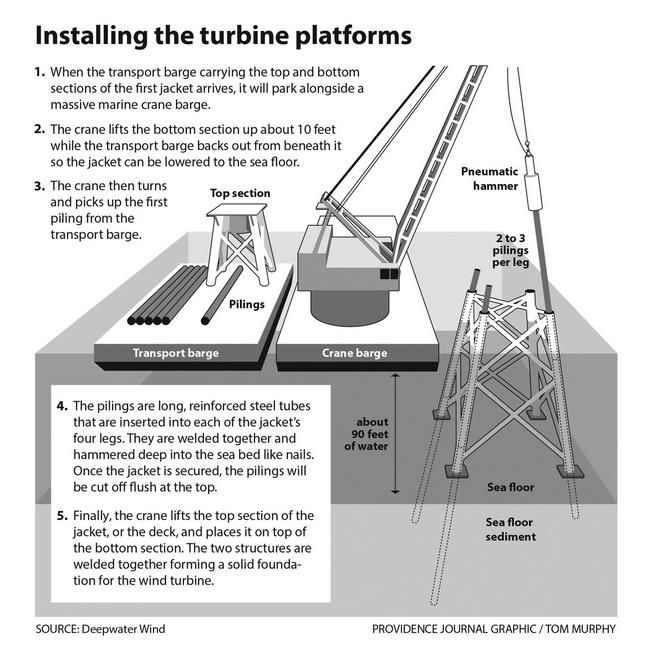

Because the 533 is the only crane that can handle the biggest pieces of the foundations — the 440-ton jackets and the 400-ton decks — it will be put to work first.

The opening sequence will go something like this: The transport barge will move into place over the site of the first foundation. The 533 will pick up the steel latticework jacket section, and while it’s suspended in mid-air, the materials barge will move out. The jacket will then be lowered down to the ocean floor and the 533 will hammer the first set of piles through its four legs and as deep as 200 feet into the seabed to anchor it in place.

The 533 can lift heavy loads but it also has to make sure it puts them in the right place. The hook on the crane is fitted with a GPS locator that ensures each jacket will be deposited within about one yard of where it’s supposed to go.

Once it’s done with the first jacket, the 533 will move on to the second jacket, and when more foundation pieces arrive, the third, fourth and fifth. Meanwhile, the 526 will take its place at the first jacket to complete the pile driving and likewise move on to do the same at the other jackets.

A few weeks in, the 533 will go back to lift the deck sections into place on top of the jackets, at which point the foundations will stand 70 to 80 feet feet above the water line and look close to the finished product.

The 571 will then come in to do the final rounds of welding, grouting and painting. Everything should be finished by late September.

Time consuming

Although the construction crews will work 24 hours a day, split into two shifts, the total project time is long because each step of the process takes time.

Take the initial lift, for example. Just freeing the first jacket from the bonds securing it to the materials barge will take six hours. Picking it up will be another four hours. It will take several more hours to pick up the piles and at least an hour each to drive them into the ocean floor.

The installation work has to be coordinated with the construction of the foundations in Louisiana. As Gulf Island Fabrication finishes pieces at its building yards in Houma, La., it loads them onto barges and sends them on their way, one by one.

The first barge left on July 4. The second one, also loaded with two jackets, one deck and piles, left July 12. The third and final barge, which will carry one jacket and three decks, is scheduled to go on July 25.

Each barge takes between two and three weeks to make the 2,100-mile journey across the Gulf of Mexico, around Florida and up the East Coast to the waters off Block Island.

If the construction of the wind farm can be divided into four broad stages — onshore construction of the foundations and wind turbines, offshore installation of the foundations, laying of a transmission cable between the wind farm, Block Island and mainland Rhode Island, and, finally, installation of the turbines atop the foundations — then Deepwater is about to enter the second. Once the work installing the foundations wraps up, Deepwater will hit the pause button.

Construction starts up again next spring and continues through the fall when the turbines should be in place and spinning away. Deepwater has spent many months ensuring that everything will line up accordingly.

In a previous career with the Dutch firm Heerema Marine Contractors, Chris van Beek, president of Deepwater, oversaw construction of the deepest floating oil platform in the world as well as one of the heaviest. Yet, he still describes the construction of the wind farm off Block Island project as complicated.

“It’s mainly complicated because it’s never been done before in the U.S.,†he said. “Doing some things here are a bit pioneering.â€

(401) 277-7457

On Twitter: @KuffnerAlex