The spans of the Margaret McDermott Bridge take shape behind a field of wildflowers. (Tom Fox, Dallas Morning News)

To assemble Dallas’ newest Calatrava-designed arches, two cranes perform a precise pas de deux with up to 100 tons of steel

In construction, it’s called a two-crane pick. Don’t let the simple name fool you. The complex maneuver requires precise execution to minimize risk and maximize safety.

As performed by workers assembling the new Santiago Calatrava arches near downtown Dallas, it’s an intricate industrial ballet, a slow-motion dance of steel using wire rope slings, shackles, spreader beams and lifting lugs, either welded on or bolted on.

Working in unison, two cranes lift and swing long arch segments into place. Some pieces weigh 100,000 pounds and more. Determining the exact center of gravity is critical.

“It’s not a job for everybody,†said Jeff Keller, a crane operator on the project.

“You have to keep your cool.â€

In 1999, the late architecture critic David Dillon wrote that the Calatrava bridges then proposed for Dallas “would add poetry and drama to a river that has never sung.â€

As much art as engineering, the Margaret Hunt Hill Bridge opened 13 years later. Its 40-story arch and curving cables grace one end of Woodall Rodgers Freeway.

Now, more poetry is emerging from both sides of the Trinity River, this time alongside Interstate 30 in view of hundreds of thousands of motorists every day.

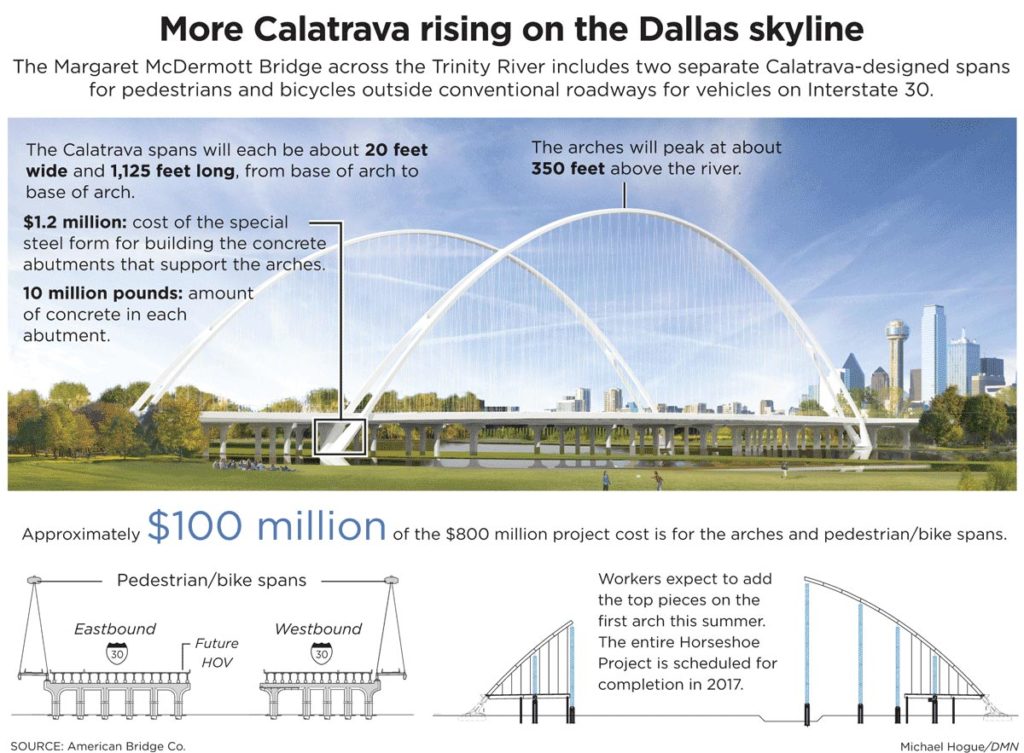

Rain and flooding have slowed progress recently, but the project remains on schedule. Eventually, twin white arches of the Margaret McDermott Bridge will reach nearly 350 feet above the water and support spans for bikes and pedestrians outside the vehicle lanes.

Five things to know about the Horseshoe project

1. The ongoing project to rebuild the intersection of I-35E and I-30 in downtown Dallas, code named the Horseshoe, will cost $800 million and take four years to complete. At peak times, about 700 workers, including subcontractors, are on the project.

2. Workers currently are assembling the twin white arches of the Margaret McDermott Bridge, which will reach nearly 350 feet above the water when complete and support spans for bikes and pedestrians outside the vehicle lanes.

3. When finished, the spans will each be about 20 feet wide and 1,125 feet long from base of arch to base of arch. Each arch will stretch about 1,290 feet. Their hollow interiors have stairs and will be fitted with permanent lighting so workers can make periodic inspections.

4. By the time workers fully assemble the arches, they will have attached more than 9,000 nuts and washers on bolts measuring 1¼ inches in diameter and 3½ inches long. At roughly $4 for each assembly, that is more than $35,000 just for fasteners.

5. The workers labor for American Bridge Co., a firm with a long résumé of construction landmarks, including the Panama Canal and the Empire State Building. Founded in 1900 and once part of United States Steel, Pennsylvania-based American Bridge also has helped build the Houston Astrodome, the Alaska pipeline, the vehicle assembly building at Kennedy Space Center and dozens of crossings of the Mississippi River.

Again, art runs headlong into industry. These new arches are being built by about 30 union workers, wearing hard hats and hard-toed boots, carrying welding torches and power wrenches.

Those wrenches — pneumatic Ingersoll Rand 2940s — are important. By the time workers fully assemble the arches, they will have attached more than 9,000 nuts and washers on bolts 1¼ inches in diameter and 3½ inches long. At roughly $4 for each assembly, that is more than $35,000 just for fasteners.

The workers labor for American Bridge Co., a firm with a long résumé of construction landmarks, including the Panama Canal and the Empire State Building.

“You always feel better when you have steel in the air,†said Adam Roebuck, the 31-year-old project manager for American Bridge.

“Steel in the air†is construction talk for visible progress, those arch segments curving upward after many, many months of important, but largely invisible, planning and preparation.

Roebuck came to Dallas after six years in California working on a new section of the Bay Bridge from Oakland. Directly in charge of a project for the first time, the University of Pittsburgh graduate has an opportunity to make his mark.

“I can go back in 20 years and say I had a small part in building this,†he said.

Typically, Roebuck said, field engineers stay on a project a few years, then pack up and move to the next job. They generally rent apartments and don’t buy.

Recent rains have flooded the Trinity River bottoms near downtown Dallas and slowed work on the Margaret McDermott Bridge (Tom Fox, Dallas Morning News)

Big dimensions

Bridges are not like snowflakes, Roebuck said, meaning there is some similarity among them. But the larger the bridge, the more distinctive it is. Cue Calatrava.

When finished, the spans will each be about 20 feet wide and 1,125 feet long from base of arch to base of arch. Each arch will stretch about 1,290 feet. Their hollow interiors have stairs and will be fitted with permanent lighting so workers can make periodic inspections, Roebuck said.

Steel for the arch and superstructure deck in each span weighs 1,720 tons.

So far, Roebuck’s crew has produced more than 2,000 pages of drawings, which translate the vision of architects and engineers into detailed plans for assembly, including the falsework towers that support the arches as they are erected.

“The designers don’t tell American Bridge how to build the bridge,†said Bob Stevens of Pegasus Link Constructors, the main contractor for the reconstruction of the interstate interchange. “They just tell them how it’s supposed to look when it’s done.â€

The engineer of record on the McDermott Bridge arches is Charles Quade, a vice president with Huitt-Zollars, an architecture and design firm. He had the same role on the Margaret Hunt Hill Bridge. Basically, he makes sure everything is done right.

Quade said that when the falsework, which provides support during construction, is removed and the full loads shift to the structures, each pedestrian bridge will “settle, or drop.â€

Drop?

“It will drop,†Quade said.

When loaded, the arches will drop, or deflect, or displace — take your pick of terms — about 7 inches; the exterior girders on the pedestrian decks will drop about 16 inches.

A primary task for Quade is coordinating all the players, including the city of Dallas and the Texas Department of Transportation, which plans and operates the state’s roads.

In the formal communications process, American Bridge’s drawings go to Pegasus Link, TxDOT, Huitt-Zollars and Calatrava, Quade said. They are reviewed and comments are exchanged.

“And Adam [Roebuck] and I will talk together, making it better to streamline the process,†Quade said.

Nobody wants a bottleneck.

Pegasus Link is a joint venture between Irving-based Fluor Corp., one of the largest construction and engineering companies in the country, and Atlanta-based Balfour Beatty Infrastructure. Overall, the Horseshoe Project remaking the intersection of I-35E and I-30 is an $800 million job scheduled for completion in 2017. At peak times, Stevens said, about 700 workers, including subcontractors, are on the project.

The Dallas Morning News has been following construction since it began. A story last summer featured the concrete batch plant located on the former Burnett Field near I-35E.

The connected arch segments comprising the ‘dog leg’ segments, EA4 north, EA4 south, EA5 north and EA4 south, are lifted into place on the new signature Margaret McDermott Bridge alongside eastbound Interstate 30 near downtown Dallas, early Wednesday, April 8, 2015. The new Santiago Calatrava designed bridge will give pedestrian and bicycle access in and out of downtown Dallas, the floodway and Oak Cliff. (Tom Fox, Dallas Morning News)

One piece at a time

The marquee Calatrava spans account for roughly $100 million of the Horseshoe project total, including the steel arch pieces, fabricated by Tampa Steel Erecting Co. in Florida. Each arch piece is trucked to Dallas as it is needed. (Steel for the Margaret Hunt Hill Bridge was made in Italy.)

That ship-when-needed strategy paid off when the Trinity flooded its banks. Only two pre-assembled arch pieces were submerged, each consisting of three segments. Roebuck said the pieces are heavy enough that there is no worry they will float away. Before they are installed, he said, they will be thoroughly washed inside and out to remove any debris left by receding water.

Founded in 1900 and once part of United States Steel, Pennsylvania-based American Bridge has helped build the Houston Astrodome, the Alaska pipeline, the vehicle assembly building at Kennedy Space Center and dozens of crossings of the Mississippi River, literally stitching together the two halves of the United States.

In Texas, the company has built nine other bridges, including the Corpus Christi Harbor Bridge, completed in 1959.

American Bridge and Fluor were partners on the new Bay Bridge span in California. Keller, the crane operator and a 42-year veteran of the industry, worked on that project, too.

Fluor and American Bridge are also partners on the new Tappan Zee Bridge in New York.

Typically, Stevens and Roebuck said, American Bridge is an equity partner in a construction joint venture, not a subcontractor as on this project. But the uniqueness of the Calatrava spans was appealing, as was the familiarity of the main contractor.

“If Fluor didn’t do the Horseshoe, American Bridge wouldn’t be in,†Stevens said.

When David Dillon wrote his critique years ago in The News, there were plans for as many as five Calatrava bridges, including on I-35E and an even higher, more elaborate span for I-30. Since then, plans have been scaled back.

While the I-30 crossing will be called the Margaret McDermott Bridge, singular, it encompasses more than one structure. In addition to the Calatrava spans for pedestrians and bicycles, there are separate, conventional spans for motor vehicles.

American Bridge crane operator Jeff Keller knocks off the mud before crawling into the cab of his crane as he works on the new signature Margaret McDermott Bridge alongside eastbound Interstate 30 near downtown Dallas. (Tom Fox, Dallas Morning News)

Concrete feet

The massive anchors for the twin arches are more prose than poetry. Four abutments each contain about 10 million pounds of concrete, including drilled shafts that extend as deep as 90 feet into the floodplain between the levees.

Pegasus Link started building the abutm

ents more than a year ago using a custom steel form to shape the concrete. Because of the unusual nature of the project, it’s possible that the form, which cost about $1.2 million, will be used only on this job.

A more typical form, Stevens said, would cost about a tenth as much and could be used on many jobs.

Embedded in each abutment are 78 anchor rods, each 10 feet long and 1¼ inches or so in diameter. They align with holes in the first arch segments.

From the base, each arch begins as two thick strands that come together briefly, then separate again and rejoin higher.

On a sunny Saturday morning a few weeks ago, workers installed a piece that looked like a giant tuning fork — on the west side of the river, south of the traffic lanes. The day was calm. Lifts are limited when wind exceeds 20 mph and not attempted when it’s over 30 mph, Roebuck said.

The segment was 105 feet long and weighed 195,000 pounds. Just before the lift, Keller cleaned the windows of his cab, front, sides and top.

“There was dew on the windows and pollen in the air,†he explained later.

A crewman removes a piece of wood stuck to the bottom of a segment as two cranes lift it into place on the new signature Margaret McDermott Bridge alongside eastbound Interstate 30. (Tom Fox, Dallas Morning News)

Over the next 80 minutes, as traffic rolled past on I-30, the crane operators and other workers guided the piece into place through a series of 100-ton pirouettes. Lift. Swing. Turn. Lift. Swing. Turn. And again, always trying to keep the piece at the same angle at which it would be installed.

A half-dozen workers, including two inside the openings of segments already in place, were on the lower falsework tower. Final adjustments were radioed to the crane operators. Two workers on the upper tower aligned the segment there.

When the piece was almost in place, an Emirates Airbus A380 flew directly overhead. It was on its way from Dallas/Fort Worth International Airport to Dubai. Pure serendipity. Still, a nice nod to the bridge project from the world’s largest passenger plane.

A little later, from inside the arch, the sound of workers pounding on pins to help align the bolt holes could be heard.

If all goes as planned, Roebuck says, his crew will place the top section — actually several pre-assembled segments equaling the length of a football field — of the first arch by late June or so. Then the cables will be attached, the decking completed.

And it’s on to the other arch, which should be completed next year.

Keller, the crane operator, said he has kept a scrapbook of all his projects — his “résumé,†he calls it — for more than four decades. When he’s finished here, his scrapbook will include photos of the soaring twin arches.

“They’re going to be part of the skyline of Dallas,†Keller said.

Republished from The Dallas Morning News – “Heavy Metal Ballet” by Gary Jacobson, Published May 29, 2015